When you think of the American Revolution, you might picture the cobbled streets of Boston or the battlefields of Yorktown. But did you know that Washington County, New York, played a critical role in shaping the outcome of the fight for independence?

This corner of upstate New York wasn’t just a bystander, it was a staging ground, a battleground, and a strategic lifeline in the struggle for freedom.

Some of the Revolution’s most famous names — Benedict Arnold, Ethan Allen, and the Marquis de Lafayette — spent time here, planned campaigns here, or fought to protect this land. Their stories, woven through the forts, rivers, and villages of Washington County, bring the drama of America’s founding closer to home.

As we celebrate the 250th anniversary of American independence, it’s the perfect time to rediscover the national legends who made their mark right here in our backyard — and to uncover how Washington County helped turn the dream of liberty into reality.

Let’s meet the patriots and freedom fighters whose courage, daring, and vision echo across our fields and forests to this day.

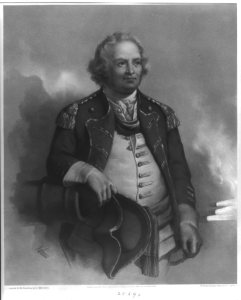

Israel Putnam – “Old Put” and the Frontier Hero

General Israel Putnam was a legendary figure of the Revolution, famed for his courage at the Battle of Bunker Hill and other early engagements. As one of George Washington’s first major generals, “Old Put” became part of American folklore. At Bunker Hill in 1775, Putnam was one of the primary commanders, and popular history credits him with the famous order, “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes,” to conserve the militiamen’s ammo.

Washington County Connection: Decades before Washington County bore that name, young Putnam trekked through its wilderness as a Ranger. In 1757–58, he was stationed at Fort Edward’s Rogers Island. There, Putnam helped famed scout Robert Rogers train provincial rangers. On one occasion, a fire broke out near the fort’s powder magazine. Putnam braved the flames to douse the blaze, preventing an explosion, though he suffered burns for his efforts.

In 1758, while operating near Crown Point/Ticonderoga just north of the county, Putnam was captured by French-allied Mohawks and tied to a stake – only to be saved at the last moment by a rainstorm and French intercession.

Such feats of bravery, along with tales of him crawling into a wolf’s den to kill a marauding wolf, earned Putnam a reputation as a larger-than-life folk hero across the colonies.

Pictured: The Murder of Miss Jane McCrea A.D. 1777 [Library of Congress]

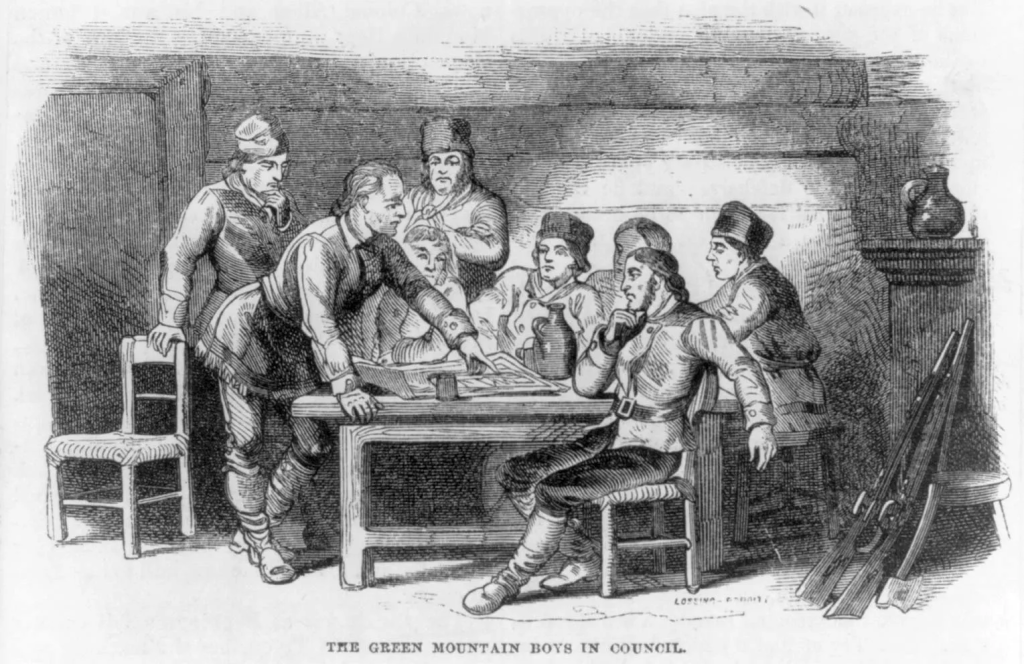

Ethan Allen – Green Mountain Rebel and Freedom Fighter

Fiery and independent-minded, Ethan Allen is best known for leading the Green Mountain Boys to capture Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775 – the fledgling Revolution’s first offensive victory.

This bold stroke was more than just a morale boost – the fall of Ticonderoga yielded a treasure trove of cannon and powder that the Patriots soon hauled to Boston, helping drive the British from that city.

Washington County Connection: At the time of Allen’s exploits, the triumph at Fort Ticonderoga unfolded right on our region’s doorstep, acting as a key defense of New York’s Champlain-Hudson corridor. In the operation’s aftermath, Allen’s compatriots moved swiftly to secure surrounding targets.

Within days, Allen’s Green Mountain Boys had captured Fort Crown Point, and Patriot militia raided Skenesborough (now Whitehall), seizing a British schooner and supplies from Loyalist Major Philip Skene.

By taking Skenesborough – the southernmost port on Lake Champlain – the patriots gained control of a strategic gateway to the lake.

All told, Ethan Allen’s audacious actions brought national attention to our region, and the cannons he helped capture thundered for American independence – a point of pride for Washington County as we remember the Revolution’s 250th anniversary.

Pictured: Ethan Allen (standing left, foreground) at a meeting of the Green Mountain Boys [Library of Congress]

Benedict Arnold – Hero of Saratoga Turned Infamous Traitor

Benedict Arnold’s legacy is a complicated tale of heroism and treachery.

In the first half of the war, Arnold was arguably one of the Continental Army’s most daring battlefield commanders. He fought with Ethan Allen at Ticonderoga in 1775, led a grueling expedition through Maine to attack Quebec, and masterminded the first American naval squadron on Lake Champlain.

His finest hour came in 1777 during the Saratoga campaign, just south of Washington County. At Bemis Heights, Arnold, though under Gen. Gates’s command, couldn’t be kept out of the fight. He charged onto the field and played a pivotal role in the American victory, rallying troops and overrunning key British positions while suffering a severe leg wound.

That victory at Saratoga, considered the war’s turning point, was in no small part due to Arnold’s battlefield brilliance, which earned him widespread acclaim as “the most brilliant soldier of the Continental Army,” as one monument later attested.

But Arnold’s story took a tragic turn. Feeling underappreciated and deep in debt, he famously betrayed the Patriot cause in 1780, plotting to surrender West Point to the British.

His treason shocked the nation. “Benedict Arnold” became synonymous with “traitor,” overshadowing his earlier feats. Despite this infamy, Arnold’s early contributions were crucial to American success.

Even today, at Saratoga National Historical Park, the striking Boot Monument honors the unnamed general who was wounded commanding American troops – a silent tribute to Arnold’s heroism that omits his name but immortalizes his “most brilliant” performance for the Revolution.

Washington County Connection: Our area saw both the best and worst of Benedict Arnold. In 1776, it was at the Patriot shipyards in Skenesborough (Whitehall) that Arnold oversaw the construction of the tiny American fleet that would fight on Valcour Island.

All summer, sawmills and forges at Skenesborough buzzed as Arnold drove his men to build sloops and gundalows. That local effort produced ships like the Enterprise and Liberty, which sailed forth under Arnold’s command to challenge the Royal Navy.

Though outgunned, Arnold’s flotilla fought bravely, and when it was finally overpowered, he ordered the remaining American ships run aground and burned at Arnold Bay – denying the British prizes and retreating through the wilderness to Fort Edward.

The following year, as British General Burgoyne invaded from the north, Arnold again raced through our region. After the fall of Fort Ticonderoga in July 1777, American forces retreated through Fort Anne and Fort Edward in Washington County. Arnold, then a Continental general, passed through these forts on his way west to relieve the siege of Fort Stanwix, then returned east in time for the Battles of Saratoga.

Ironically, Washington County also felt the sting of Arnold’s treason: While our area escaped Arnold’s later wrath, locals at the time felt deeply betrayed that the hero of Ticonderoga and Saratoga, who had once fought on our soil for American freedom, had sold out to the enemy.

Today, we remember both halves of Arnold’s legacy: the fearless Patriot defender of our region in 1776–77, and the cautionary tale of ambition gone astray.

Pictured: Gen. Arnold wounded in the attack on the Hessian redoubt by Alonzo Chappel. [New York Public Library Digital Collections]

Robert Rogers – Frontier Ranger and Tactician

Robert Rogers first rose to fame in the French and Indian War, long before independence, as the intrepid leader of Rogers’ Rangers. This elite ranger corps specialized in frontier warfare – quick strikes, scouting, and survival in the wilderness – and Rogers literally wrote the book on it.

His 28 “Rules of Ranging” laid out guidelines for guerrilla tactics and discipline. These principles were so effective that they are still studied by modern U.S. Army Rangers, who revere Rogers as a sort of founding father of their branch.

Rogers became a frontier legend, renowned for his rugged endurance and cunning strategies. When the Revolution broke out, Rogers was living in America and initially offered his services to General Washington, but the Continental Congress doubted the loyalties of this former redcoat ranger.

Indeed, by 1776, Rogers had switched allegiance to the Crown, raising the Queen’s Rangers regiment for the British. Though a Loyalist in the end, Robert Rogers’ earlier contributions to irregular warfare left a lasting imprint on the American military tradition.

Pictured: A monument to Robert Rogers at Rogers Island in Fort Edward, NY

Washington County Connection: Rogers’ personal story and Washington County’s history are tightly intertwined at one critical place: Rogers Island. This island (now part of the town of Fort Edward) was the Rangers’ main base of operations during the French and Indian War.

In the winters of 1757 and 1758, Major Rogers and his band of New England woodsmen encamped on that very island, training and launching raids into the Adirondack wilds. It was here that Rogers reputedly penned his “Rules of Ranging”, taking lessons learned in bloody skirmishes and codifying them for others. Local lore tells of Rogers drilling his men in the snow and forests along the Hudson’s banks and returning after long scouts to warm themselves by the fort’s fires.

The island became a hotbed of frontier innovation as, essentially, America’s first special forces training camp.

Years later, during the Revolution, Fort Edward again saw Rogers in action, but this time covertly. In 1777, as Burgoyne’s forces occupied Fort Edward, Rogers (by then a British officer) may have returned to his old haunt, possibly as a spy or scout for the Redcoats.

Today, Rogers Island in Washington County hosts a visitors’ center and archaeological sites that celebrate the Ranger legacy. Each year, reenactors gather to honor Rogers’ pioneering tactics.

While Rogers himself fought for the British in the end, Washington County proudly claims its share of his wilderness legend – a legacy of frontier resilience and tactical ingenuity that echoes in the U.S. Army Rangers to this day.

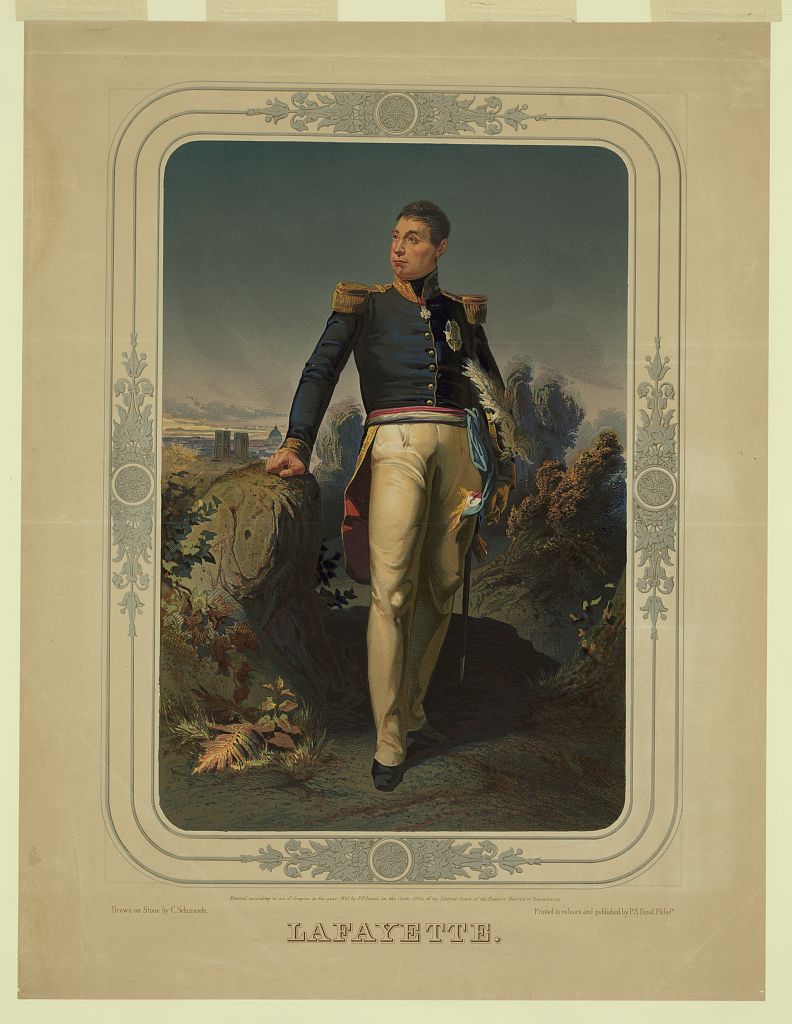

Marquis de Lafayette – French Ally and Adopted Son of America

The Marquis de Lafayette, a young French aristocrat, became one of the Revolution’s most celebrated heroes: a foreign volunteer who truly earned the title “Hero of Two Worlds.”

Lafayette’s story is the stuff of adventure: at just 19, inspired by the American cause, he sailed across the ocean in 1777 to offer his services to General Washington.

Congress made him a major general, and Lafayette formed a close “father-son” bond with Washington. He saw his first action at the Battle of Brandywine in Pennsylvania, where he was shot in the leg yet helped organize an orderly Patriot retreat amidst the defeat.

Lafayette’s most crucial contribution came when he returned to France, where, thanks in part to his influence, they agreed to a formal alliance, sending troops and a fleet that proved decisive.

In 1781, Lafayette commanded American forces in Virginia, skillfully hemming in Lord Cornwallis’s British army at Yorktown until the main French-American army arrived. His troops essentially cornered Cornwallis by blocking escape routes, directly leading to the British surrender at Yorktown – and ultimate American victory.

When he died in 1834, he was buried under soil from Bunker Hill, forever linking him to the country he helped make free.

Washington County Connection: During the war, in February 1778, Lafayette traveled to Albany to assume command of a planned expedition against British Canada, but arrived to find the scheme in disarray. But before departing, Lafayette made a notable impact in our region: he succeeded in recruiting members of the Oneida Indian Nation to support the American cause.

Lafayette’s most direct connection to our county came in 1824-1825, during the 50th anniversary of the Revolution. Invited by President Monroe, the 67-year-old Lafayette toured all 24 American states as the nation’s guest. He traveled up the Hudson River to Albany, then on to Vermont. Records show he was met with rapturous receptions everywhere: Americans adored him for his wartime service.

While we’re not sure where he set foot in Washington County specifically, local communities from Albany to Whitehall celebrated Lafayette’s return.

Pictured: The Marquis de Lafayette in uniform by C. Schuessele [Library of Congress]

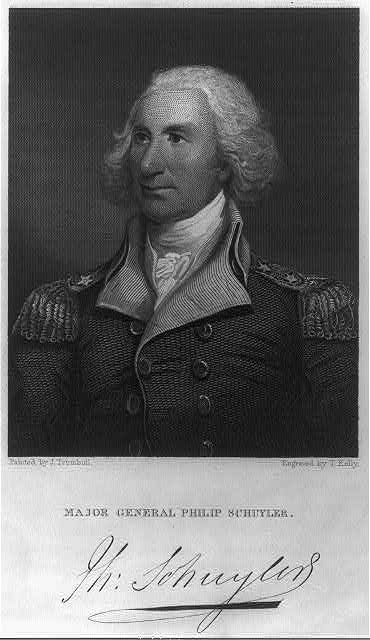

Philip Schuyler – The Strategist of the North

Major General Philip Schuyler was one of the highest-ranking New Yorkers in the Continental Army and a crucial organizer of the American war effort in the North.

Major General Philip Schuyler was one of the highest-ranking New Yorkers in the Continental Army and a crucial organizer of the American war effort in the North.

He oversaw early attempts to invade Canada and, in 1777, was responsible for defending New York against Burgoyne’s grand invasion from Canada. Though Schuyler had fewer famous battlefield moments, he was the architect of the strategy that ultimately defeated Burgoyne.

By late summer 1777, Schuyler’s efforts had nearly stalled Burgoyne’s army as it pushed south. However, Congress, eager for a victory, replaced Schuyler with General Horatio Gates just weeks before the culminating Battle of Saratoga. Ever the patriot, Schuyler put aside any personal resentment and fully supported Gates and Benedict Arnold in the fight that October.

Washington County Connection: Washington County was Philip Schuyler’s military backyard in 1777. Throughout that summer, General Schuyler had his headquarters at Fort Edward, directing the defense of the region. It was Schuyler who made the tough call to abandon the fortress of Fort Ticonderoga when British forces flanked it.

As American soldiers fell back through Whitehall and Fort Anne to Fort Edward, Schuyler orchestrated rear-guard actions and the obstruction of roads. Under his orders, locals chopped down trees to block the British advance along the forest paths and burned supplies that couldn’t be carried off.

One infamous event during this retreat was the death of Jane McCrea near Fort Edward: a young woman engaged to a Loyalist officer who was killed by Burgoyne’s Native allies. The news of her slaying spread like wildfire, and Schuyler used it to rally angry frontier militiamen to join the American army.

By mid-August 1777, Schuyler had gathered a large militia force in the Washington County area, which set the stage for the victories at Bennington and Saratoga.

In our local story, Schuyler is very much the hero behind the scenes – the general who turned Washington County into a defensive bulwark. Even after he left the army, Schuyler remained connected to the area, overseeing reparations for war damages and supporting frontier communities.

Schuyler’s legacy looms large here. We remember him as the master strategist and beloved patriarch whose foresight and sacrifice helped ensure that the revolutionary flame in Washington County did not flicker out during the darkest days of 1777.

John Stark – Hero of Bennington and New Hampshire’s Champion

General John Stark embodied the fighting spirit of the independent New Englander. A veteran of the French and Indian War like Putnam and Rogers, Stark earned everlasting fame in the Revolution as the “Hero of Bennington.”

Born in New Hampshire, Stark had fought at Bunker Hill and Trenton, but his greatest moment came in August 1777, when he led a band of New Hampshire and Vermont militia against a detachment of Burgoyne’s army near Bennington. Stark’s farmers-turned-soldiers overwhelmingly defeated a force of Hessian mercenaries and Loyalists, capturing nearly 1,000 enemies.

The Battle of Bennington was a crucial American victory. It deprived Burgoyne of supplies and reduced his army by about 15%, directly contributing to his surrender at Saratoga weeks later.

Washington County Connection: The Battle of Bennington might bear Vermont’s name, but much of it was actually fought in present-day New York, not far from Washington County’s southwest corner. In August 1777, General Stark marched his militia across what is now Washington County to reach the area of Hoosick, NY.

Washington County Connection: The Battle of Bennington might bear Vermont’s name, but much of it was actually fought in present-day New York, not far from Washington County’s southwest corner. In August 1777, General Stark marched his militia across what is now Washington County to reach the area of Hoosick, NY.

There, on August 16, he surprised Burgoyne’s enemy force that had been sent to raid rebel supplies. Many Washington County men were in Stark’s ranks that day. Farmers from places like Cambridge, Salem, and Jackson answered the call to defend their homes from Burgoyne’s foragers. They joined Stark’s New Hampshire men and fought in the woods along the Walloomsac River, attacking from both sides.

Stark’s victory electrified the region.

Local Patriot leaders breathed a sigh of relief as news spread that Burgoyne’s feared Hessians had been defeated at our doorstep. In the battle’s aftermath, wounded soldiers from both sides were brought into villages like Cambridge and Greenwich for care, and captured British equipment was carted off through our county on its way to American depots.

Years later, the aging Stark reminisced about Bennington in a famous letter to his comrades, toasting, “Live free or die: Death is not the worst of evils.”

Pictured: The Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site in nearby Hoosick Falls, NY

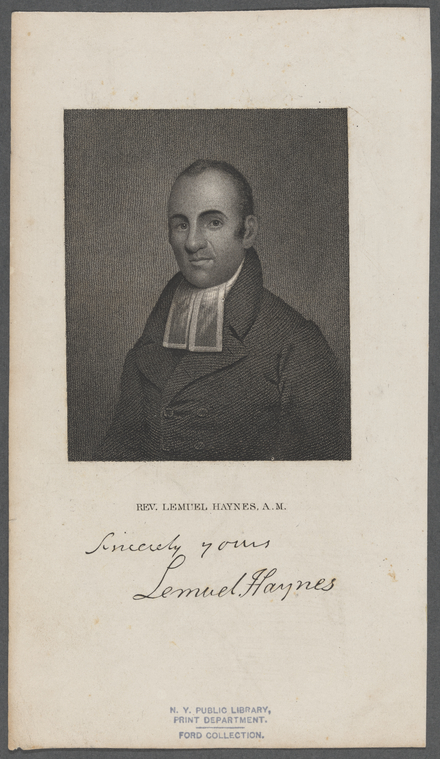

Lemuel Haynes – Black Patriot and Voice for Freedom

Lemuel Haynes may not be as famous as generals and statesmen, but his story is profoundly significant in the context of the American Revolution. An African American raised as an indentured servant, Haynes became the first ordained Black minister in the United States and a pioneering voice for abolition, all as a veteran of the Revolutionary War.

Born in Connecticut of mixed African and European ancestry, Haynes was indentured in Massachusetts, where he taught himself to read and write. When the Revolution broke out, he enlisted in the local militia. Haynes marched as a Minuteman in 1775 after Lexington and Concord, and in 1776 he served at the garrison of Fort Ticonderoga, which the Americans had captured from the British.

Born in Connecticut of mixed African and European ancestry, Haynes was indentured in Massachusetts, where he taught himself to read and write. When the Revolution broke out, he enlisted in the local militia. Haynes marched as a Minuteman in 1775 after Lexington and Concord, and in 1776 he served at the garrison of Fort Ticonderoga, which the Americans had captured from the British.

During lulls in duty, Haynes mused on the meaning of liberty. In 1776, inspired by the Declaration of Independence, he penned an essay entitled “Liberty Further Extended,” an eloquent argument that the principles of the Revolution should apply to enslaved people as well, making it one of the earliest anti-slavery tracts in America.

After his military service, Haynes pursued Christian ministry. In 1785, he was ordained in the Congregational Church, marking the first time an African American attained that status. He went on to minister to predominantly white congregations for decades, challenging racial barriers of the era. Nationally, Rev. Lemuel Haynes is remembered as a true patriot-preacher: A man who fought for his country’s freedom and then urged his country to live up to its ideals of equality.

Washington County Connection: Remarkably, Washington County became Lemuel Haynes’s home for the final decade of his life, and it’s where he left an enduring local legacy. In 1822, at age 79, Haynes was invited to become pastor of the South Granville Congregational Church, a small church in a rural corner of Washington County.

He moved here with his family and preached to the congregation for eleven years, until his death in 1833. Despite his advanced age, Haynes was known to climb into the pulpit with the same passion and conviction that had defined his earlier ministry.

Locals, almost all of them white farmers, revered “Father Haynes” for his wisdom, humility, and dedication. Under his guidance, the South Granville church likely heard some of the earliest anti-slavery sermons delivered in upstate New York. He also taught and mentored youth in the area, making an impression on the next generation.

Washington County holds deep pride that such a remarkable patriot and preacher spent his twilight years among us. The Lemuel Haynes House in South Granville, where he lived, is today a National Historic Landmark, a tangible reminder that the ideals of the American Revolution (liberty, equality, and faith in justice) found a champion here in Washington County.

As we celebrate 250 years of independence, Haynes’s story resonates strongly, illustrating that the Revolution was fought not just on battlefields, but in hearts and minds, across racial lines, and on our Main Streets in Washington County.

Pictured: Portrait of Rev. Lemuel Haynes and facsimile signature. [The New York Public Library Digital Collections]

Washington County’s Revolutionary Spirit: A Legacy That Lives On

From the bold raids of Ethan Allen to the battle-hardened leadership of Israel Putnam and the complicated heroism of Benedict Arnold, Washington County’s story is inseparable from the larger story of America’s birth. Here, the wilderness became a war zone. Forts and towns rose and fell. Roads were cut through forests, not just for trade, but for the march toward freedom.

Today, Washington County stands as more than just a picturesque place: it’s a living museum of the Revolution’s struggles and ideals.

The patriots and figures connected to this region weren’t just footnotes — they were game-changers. Their footsteps still echo here. Their courage still inspires. And their legacy is more important to remember now than ever.

In the years ahead, our communities will host reenactments, exhibits, and school programs to honor this legacy.

When you walk the grounds of Fort Edward or Fort Ann, or gaze upon the Hudson at Rogers Island, you’re walking in the footsteps of Putnam, Schuyler, and Rogers. A drive past the pastureland near Walloomsac recalls Stark’s triumphant charge at Bennington. A visit to Fort Ticonderoga conjures images of Ethan Allen’s musket at dawn and the cheers of victory that echoed down the lake. In Whitehall, you can envision Arnold’s ragtag fleet taking shape. In Granville, the preserved Haynes House stands as a testament that the struggle for freedom included voices that would inspire abolition and civil rights.

The 250th anniversary is not just a time to recount dates and battles, but to connect with the human drama of the Revolution: the bravery, sacrifice, and ideals that defined our nation’s birth.

Other Famous Figures Tied to Washington County

Henry Knox’s “Noble Train of Artillery” rolled right through Washington County

In 1775, young artillery expert Henry Knox hauled 60 tons of cannons — captured from Fort Ticonderoga — through icy lakes, snowy forests, and muddy trails. His route passed right through today’s Washington County, delivering the firepower George Washington needed to drive the British out of Boston. No cannons, no independence!

Alexander Hamilton had family ties to the Washington County region

Hamilton, then a young aide-de-camp to Washington, was deeply involved in logistics for the Northern Army during the critical campaigns of 1777

When Hamilton married Elizabeth Schuyler in 1780, he gained not just a brilliant wife, but strong connections to General Philip Schuyler’s many New York estates. The Schuyler family holdings stretched into parts of today’s Washington County, meaning America’s most famous founding father-in-law had boots on the ground near Fort Edward!

General Horatio Gates commanded the American Northern Army from Fort Edward

Before the American victory at Saratoga, General Gates made Fort Edward his strategic headquarters. He orchestrated the defense of New York from these very grounds, proving that Washington County wasn’t just close to the action — it was the action.

Daniel Morgan and his famous Virginia riflemen marched through Washington County

Known for their deadly marksmanship, Morgan’s men camped near Fort Edward as they raced north to join the fight at Saratoga. Their sharp shooting would help cripple British forces — turning the tide of the entire war!

And there’s no Washington County without Washington!

George Washington may never have camped under the stars in Washington County himself, but his presence was felt everywhere.

The defense of Fort Edward, Fort Ann, and Skenesborough was a top priority in Washington’s wartime strategy. He directed troop movements and supply lines that flowed through the region, relying on generals like Philip Schuyler and Horatio Gates to protect this vital frontier.

The renaming of Charlotte County to Washington County in 1784 was a symbolic gesture: honoring the man who led the Revolution, and recognizing how crucial our region had been to the fight for independence.